Dragons

Originally the Dragons of this world were merely animals, hardly anything more than eating machines similar to sharks. The Gods came, and changed all that. Genetically engineered, perhaps magically altered, these creatures became something far more than they had been.

Dragons live for thousands of years, easily into the tens of thousands and in some cases may very well be truly immortal. Their origins as underwater creatures bears this out, as many fish similar to sharks can live for hundreds of years and simply keep growing as long as there is adequate food for them. The Dragons were already such long-lived and ever-growing creatures. All Dragons are capable of life above and below the surface of water easily.

Female Dragons lay their fertilized eggs on the sea floor. The shells are soft but very thick, and sometimes take up to a decade to mature enough to hatch. The eggs are generally around one foot wide, though some locations of hatcheries encourage smaller, but more plentiful egg laying, while others allow for huge meter-wide eggs. Also in general, the eggs of an older female will be larger and healthier than those of a younger less experienced female. The warm vents where the Dragons prefer to lay move nutrients all over the shell, which is porous and allows plenty of things in, while keeping out hostiles.

Females lay from five to twenty eggs at a time, more if there is plentiful food and warmth, less if they are smaller or inexperienced. Dragon parents do not nurture their young. They have no need to, as their young will not even recognize them from food, at that stage of their lives.

The baby Dragon hatchlings emerge from their leathery shells hungry but ready to hunt. With highly developed senses of electric and magical means, as well as a profound sense of smell with which to locate prey, they automatically begin seeking out whatever they can reach. At this stage in their lives they are little more than tadpoles: a large toothy mouth and a long, eel-like body. They run from a little more than a foot long to more than six feet at hatching, depending on their location, breed and mother’s influence. They have no ‘facial features’ at this stage and if they are lifted too quickly out of the depths they may die, and will certainly always be stunted.

For many years, young Dragons swim in the rich deep ocean. As they mature their bodies gain fins, which allows them to move more swiftly. They spend at least twenty years in their hatching depths, and in fact many of their waste products filter down to feed their un-hatched siblings below.

As the Dragonlings fins mature, their skin begins to harden into the familiar shark-like leather that they all sport as adults. However they have at least half a century to go before they’re considered even a fledgling! Over time, their fins begin to solidify into limb shapes. The more nutrients they eat, the quicker this process can be finished. Calcium is found in many places below the surface, but the best source they’ve found is of course, other fish. They do not cannibalize, except in extremely rare cases where there is literally nothing else to eat. (The only known causes of this were when the Gods were experimenting, and when the Rebellion occurred and blasted many locations killing most of the natural food chain.)

Provided enough nutrition along this stage in their lives, Dragons will also be gaining new senses. Since they can now swim higher into the surface areas, their eyes begin to form. Also they have primitive hearing, though they don’t truly gain that sense until they come out of the water. In the dim light far below the surface, there are plenty of bioluminescent creatures, and those are generally the first things that a young Dragon sees. And eats.

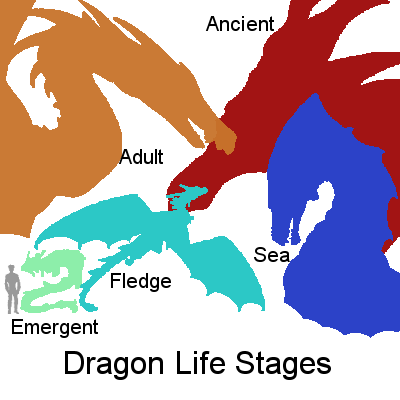

Wing buds begin forming when the Dragonling is able to surface for the first time. This is not their Fledge stage, it is merely their Emergence. With limbs able to support them on land, and a fully formed body, they are often around twenty to thirty feet long, but their tail is easily half their full length. At this stage they breathe their first air, with lungs having slowly been developing during their shallows stay. Most young Dragons remain in the water during this time, even though they are capable of walking on land. Their limb strength will have to support them and some just don’t like the weight of things on the surface.

After Emergence, the skin of a Dragon thickens considerably, and grows so that it sheds on occasion. They often return to the sea after a shed, as their new skin is sensitive and needs moisture. Only those who live in jungle areas remain on land during these periods. During this transition time as well, their tail often loses much of its bulk and becomes thinner, as they adjust to life on land. However, many which go back to the sea or spend much time there remain thickly muscled and ‘tail heavy’. (These Dragons are called ‘rudderbacks’ and are often those who live exclusively in the water.)

With wings now spreading off their bodies, they can return to the water and move with incredible speed, manta-like through the water. This is of tremendous importance, since they now must feed on anything that they can, to create their full flight-capable wings and strengthen their upper bodies. The wings of a Dragon are softer than their body skin, but very durable. Many Dragons spend about ten years at this stage, though in food rich areas on land or the sea, they can spend as little as five years. Lands with plentiful game often see Dragonlings galloping through meadows chasing deer or boar. It is also during this stage when those Dragons who cannot keep up with their siblings may fall prey to other animals, even small ones, if they are not careful.

Though they are intelligent, young of any breed will do stupid things. Some try to fledge before they are ready, others try hunting creatures too dangerous for their size, and still others attempt to eat things that are just plain bad for them. In this manner perhaps a third of the hatchlings will eventually die before reaching maturity. Note well that at no time during a Dragon’s life do they have a true sense of taste. They will eat anything that they can get their mouth around, and that smells of blood. As long as they know what they’re looking at is prey, they’ll go for it. The only accidental deaths by Dragonkin eating other humanoids are when a young Dragon has not been informed of the ways of the world. Young Dragons are rarely punished if they accidentally ingest another sentient, but once they pass a certain point in their life cycle, they are expected, indeed required to know better.

When young Dragons begin to spend most of their time on dry land, their elders begin to teach them fully. Most already have a strong sense of knowledge about the world: that there are other people in it, and that they are to be treated carefully. However, they don’t know their history, they do not know languages yet, and cannot use their magic fully.

Some young Dragons are gifted with magical power before they are ready for it. This causes another significant drop in population when accidental implosions, fireballs, earth ruptures and the like claim their users. Magic is after all a dangerous and delicate thing. Without the skill and patience to use it correctly, any being is able to lose control. The Dragons see this as a trial period, if a youngling has a dangerous compulsion to use their magic, they will let it happen. Generally it weeds out those who are unable to properly interact with and command it. It also often enough weeds out those who are incapable of, or don’t desire to, get out of the way.

As their magic and wings begin truly growing, and their elders instruct them in both flight and power, a Dragon is considered a Fledge when it first lifts off from the ground with its own wings and the wind. There are better and worse ways and locations to do this. And yet again, this provides another die-off point in the lives of Dragons. Broken necks, backs, and permanently damaged wings claim many young Fledges. At this stage, a Dragon is generally from thirty to forty feet long, some evening up the difference between those laid as large eggs and smaller ones. A Dragon would rather die than live without being able to fly, if they’re inclined to head to the skies, and those with the desire to return to the sea will still be hindered by any large broken bones. Either way, they are doomed.

The Dragons’ wings will continue to grow and some even sprout extra pairs along the back of their bodies, over their hips and down their tail. The eldest and strongest of Dragons has seven pairs of wings, total, along his whole spine down to the tip of his tail (a full 350 feet from his nose). Whether he can fly at all at this point is in question, but there he is.

By the time a Dragon is around seventy to one hundred years old, they are considered fully adult. They have been educated by their elders and the Dragonkin in the ways of the world, their place in it, and the history of their kind. Dragons that live around other species often form intimate bonds of friendship with them, living as protectors, hunters and travel consultants, as well as scholars.

Dragons can speak almost any language, as they use a parrot-like voice box found in their upper nasal cavities to do so. In addition to this they can roar and make huge noises that travel over hundreds of miles. The sounds of these roars can deafen people nearby, break windows and even wood, and cause earthquake-like ripples in water and soft land. It is of no doubt that blasts like those along with fireball explosions aided the Dragons in their Rebellion. Dragons also can learn to read pretty much anything they can see, and their eyesight after they’ve fully fledged is keen but not tremendous. For creatures their size, they can easily read a normal page such as this, if it’s held around the end of their nose. But any smaller print, just cannot be focused upon and they don’t bother trying (they are not like the Griffins, who have eagle-sharp eyesight – after all, Dragons kill and eat large prey). Dragon scholars write on long sheets of leather, scrolled onto poles and turned with a crank below it, in their own unique script.

Dragons keep growing as they get older, but much more slowly than in their formative sea-born years. However, some return to the sea full time, towing boats or hunting pirates. These Dragons may reach up to twice the length of their sky-born siblings, but eventually cannot truly fly above the ground. Likewise, some Dragons remain mostly on the ground in more sedate scholarly settings, as politicians and educators, and neglect their flight abilities as well as their swimming. Many Dragon mages have small wings and rarely take to the skies. It is a true master Dragon that remains adept in the air, land and sea all at once.

There is little visible difference between a male and female Dragon. Males tend to be longer, while females tend to have more bulk around their hips, but aside from those things it’s not easy for a non-Dragon to tell them apart without knowing them personally. They have unique voices, but only choose to emulate one gender over another if they’re conversing with humanoids, and thus that’s not a good way to tell either. Dragons themselves innately ‘know’ the gender of their companions, whether this is through pheromones they are attuned to, magic emanations or telepathic communication, no one else knows. The only sure way for a non-Dragon to know is watching them fight. Dragons are not really territorial individually. But they are rather finicky about who is nearby, and unless they’re very secure in their own space, they will growl, snarl, bite, hiss and display to chase off anyone they don’t like. This is particularly notable during a female’s breed season, which may happen as often as once every few years, but is in general only once every decade at best. The females give off high-pitched screeching, creeling and cries that alert the males nearby that they are ready to mate. The males respond with booming and strident calls of their own. Anyone not interested in this display – Dragon or otherwise – is encouraged to leave the area. A female in heat is a wonder to behold but she is also extremely dangerous.

Mating dragons require a lot of space, both on land and in the air. Males will fight with one another in the air to prove themselves worthy as well as show off to the female, and females will compete for good spaces on land with other females. Woe to the area if there are two females ready in the same spot, because they do not like getting ‘second bests’ and whoever wins among the males is surely the best. A female who loses to her nearby rival will often just stop being fertile for the time being, to give herself the chance to get the ‘best’ again when she’s alone. Males on the other hand are always in a state of girded readiness, and they seem to use their now-keen hearing to listen for those high screeching cries. If a male is able to hear it, he’s going to leave off what he’s doing, to go check out not only the female but the competition. It’s imperative that all dragon males go to their females, because ignoring this call may mean no males are in the area when she is at her peak. Even the most scholarly Dragon sages give it a try, though they rarely compete if there are younger flight-worthy males around.

Those sages, and those who choose not to be on land or in the air, have a different method of finding a mate, and can afford to be more picky. Equal numbers of males and females choose this path, and their courtship often resembles humanoids with flirtation, dating, turndowns, and settling with whoever is around. The eggs that may come from these pairings are usually laid in the shallower waters, secure and safe, but with less of the nutrient rich vent-water to pass over them. It is suggested that if this continues, these Dragon-sages may become an entirely separate species since they have such different expectations and life styles. They are often smaller, but smarter, and communicate much more readily with non-Dragons. Sea-born dragons remain about the same, only the males fighting often erupt above the water and dazzles anyone nearby able to view it.

As a Dragon ages, they continue to grow but will eventually become too big to fly comfortably. Some at a later stage will return to the water, where their weight is easier to deal with and they can still hunt with ease. Though some Dragons will succumb to weather effects or natural disasters, breaking a wing or leg as an elder means that they’re just slower, but not stopped. Some Summoners and Jewel Witches have suggested they try out healing medicine and magic, but often a Dragon with a big tear in his wing will sport it as a badge of pride, a story to tell, rather than allowing it to hinder him.

The food needs of any adult Dragon are less considerable than you’d think. For a fifty-foot dragon, a single cow or similar sized meal every week will suffice. Some subsist on less than that, but many merely eat smaller things on the hoof or catch gallons of fish a day. Smaller Dragons may even pick over their food like a Human, though Dragons are essentially carnivores they may also choke down fruits and grains. Seaborne dragons often eat kelp, and there are some high airborne ones which claim to subsist only on magic. No one knows whether they’re lying or mistaken, who is going to question them?

Genetically there is tremendous variation among the Dragons. They have a variety of specific differences such as crests, fins on their legs, the shape of their head and neck, and the like. Also, their coloration varies greatly from area to area. Most of the time, a Dragon will reside where its parents did and this reinforces their features. Some travel much farther to find mates, but the bulk of Dragon-kind are localized and thus have common features to that area. Colors and patterns, as well as features will pass on to offspring and remain strong for generations.

The coloration of any given dragon is at its brightest when they are around two hundred to five hundred years old. Before then, not all their colors may be visible, or they are in a more pastel shade; their patterning might become visible gradually over decades. In their elder stage, their colors are more faded but the patterning is clearly visible. The only time these things are altered is when the Dragon is in its shed stage, the colors and patterns are always more vivid after, while before their skin sheds it is dull and muddled.

Castoff Dragon skin is a valuable commodity, particularly because it remains very thick and sturdy even after hundreds of years. Dragons don’t have any particular taboo against others using their skins in construction or clothing, as long as it was given freely or taken from a general pile – some areas of the world don’t encourage Dragons to just slough off their skin anywhere they like. Rather, they have a location like a quarry pit to discard their skins and allow them to be collected by the locals.

Likewise, occasionally a Dragon will lose a claw, tooth or spare fin in a hunt or fight. These are of less consequence to them than other creatures, since they will grow back reasonably quickly. There are no particularly special magic associated with Dragon parts, except for their entire carcass if a Necromancer happens upon it. Necromancers do not dare work their spirit magic on a Dragon, they’ve done so in the past and have learned to regret it.

Dragon interaction with other races is in general pleasant and beneficial to everyone. Obviously there are exceptions, as some Dragons resent the intrusion into their world after they fought so hard to gain control over it. Dragons enjoy company of any kind though, be it their own breed, their ‘kin’ or other species entirely. Many highly social dragons are extremely polite and observant, except when there’s a mating flight going on. They often sense the mood of a group long before they ask about it, and are surprisingly tactful.

Those who have little contact or have been ill-taught to be social by their elders are another story. Some even rampage across the countryside because they have heard Human legends of such things, there’s one in every family, right?

The Dragons hold high political sway around the world. Also since their speed and size can allow them to move very quickly through physical space, and their magic can be used to communicate over long distances instantly, they have become known as a kind of world-wide warning system. Large storm-fronts, dangerous winds, rogue wizards, even rogue Dragons are spoken of very quickly around the world.

Dragons do not have a known system of government, as they are so widespread and so ‘large and in charge’ that no one really thinks they need it. They defer, most often, to their eldest in the area and definitely to those who seem most learned or skilled. There are clearly those who would rather fight it out, and prove their ‘worth’ by taking a chunk out of their enemies or even a neighbor just to keep them in line, but those are the ones who are often shunned by their more civilized peers.

Perhaps of all the two-legged population around them, they enjoy interactions with the Grape Barony the least. Even though the Barony is filled with interesting people, it’s also mainly for herbivores. And, their culture too closely resembles the Gods’ before their fall. The Clockwork intrigue the Dragons, though they aren’t really certain quite what to do with the little robotic people. Though there is tremendous respect among the Dragons for both Summoners and Necromancers, they have a very narrow field of approval for their actions. The Summoners because they enslave others (even if temporarily) and the Necromancers because there is the danger that they will in fact begin trying to bring dead Dragons to battle the living ones. The elves of the Mossgate, particularly the Gliders have the most positive and easy relationship with the Dragons. They enjoy the simpler life of hunting and crafting, and exploration. Wyldkin have a similar interaction, however they seem to be fairly focused on their own needs rather than working with Dragons. Nomads are almost superstitious about the Dragons, and hardly interact with them because they are so magical. The Reed folk have a good bond with elders and sages. Those who make their living on the seas find a steady friend in any seagoing Dragon, and any pirates are dealt with quickly… with a bite. The Jewel Witches enjoy the company of Dragons at any stage, and outfit the most gifted with their own jewelry made specifically to enhance Draconic magic. This kind of act assures that the Witches will always be cherished by most Dragons. They have discovered that they can be commanded but not disrespected, when the Lumin need their aid – if and when the Kings call them, they know it is important.

Obviously, Dragons and Dragonkin are closely related and have a strong attachment to one another. The Dragonkin are described next.

Dragons speak only one language native to their own ‘tongues’, and telepathically communicate far more often. They have names that only they can truly pronounce, in that they are often based on volume and duration of sound rather than a set of syllables strung together. (REALLY LOUD CLICKING several soft purrs Loud Distinct Chirp is a name in Dragon.) They take nicknames, but only if they’re apt to be among another population which requires them to be addressed. They don’t mind being called ‘the yellow dragon’ or ‘that six-winged one’. They’re just as good at assigning nicknames to their humanoid companions (smells like charcoal and dust, thistle head, that one thief we ate…).

Important Dragons of the Current Era

(none yet)

Features of Dragons

• Shark-like hide with patterned coloration, that sheds on a regular basis as they age/grow

• Aquatic, terrestrial and aerial capabilities in equal amounts unless they choose to specialize

• Egg-laying, in deep waters; a female becomes fertile every few years to once in a decade or less. Females that are large lay larger, healthier eggs. For every 100 eggs laid, usually only 5-15 survive into adulthood, with die-offs at multiple stages of growth/education

• At adult age, are generally at least 50 feet long, and can grow to over 200 feet with their tail making up at least a third after adulthood

• Are good magic users, highly intelligent and civilized

• Have no sense of taste, but all other senses plus electrical and magical added

• Are not sexually dimorphic enough to allow easy sexing by most means

• Can live many thousands of years, but may be killed at any time from natural or unnatural causes

• Have specialized voice boxes within their nasal area to mimic any speech they can learn including magic

• Have a low population but live for a very long time naturally